New research on deepfake videos about the Russian invasion of Ukraine shows they distort reality and create a dangerous environment where users distrust all media. Conspiracy theories and paranoia thrive on this distrust.

Image manipulation in political propaganda is nothing new. A 1937 photograph of Joseph Stalin walking along the Moscow Canal with Nikolai Yezhov, the former Soviet secret police chief who organized the “Great Purge,” is famous. Yezhov was executed in 1940 by his own grim system. The original photo was altered to remove him and replace him with background scenery.

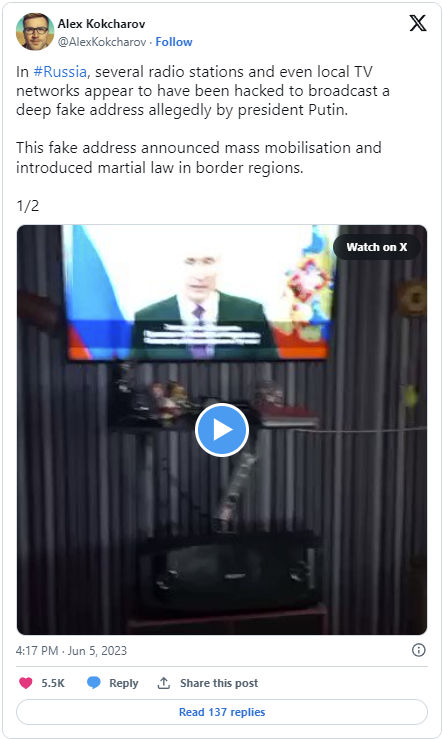

These old tricks are back thanks to technology. Social media and AI have made forged imagery more realistic and dangerous.

A new study by University College Cork in Ireland examined how users on X (formerly Twitter) responded to deepfake content during the Russian-Ukrainian war. Main takeaway: Deepfakes have caused many people to distrust wartime media to the point where nothing can be trusted.

Researchers and commentators have long worried that deepfakes could spread misinformation, undermine truth, and damage the credibility of news media. Deepfake videos could undermine what we know to be true when fake videos are believed to be authentic and vice versa, said study author Dr. Conor Linehan from University College Cork’s School of Applied Psychology.

AI is used to create false audiovisual media, often of people, called deepfakes. A common method is “pasting” a famous politician’s face onto a body video. Like a hyper-realistic virtual puppet, the producer can make the politician say and do whatever they want.

Researchers found fake Ukrainian conflict videos from all angles. In early March 2022, a deepfake of Russian President Vladimir Putin announced peace with Ukraine. Also shared were fake videos of Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelenskyy ordering his soldiers to disarm.

The Ukraine Ministry of Defence tweeted footage of “The Ghost of Kyiv” a few days after the invasion in February 2022, in another example of disinformation. It was actually Digital Combat Simulator footage.

Most of the examples in the researchers’ dataset involved media outlets mislabeling legitimate media as deepfakes.

The problem is that deepfakes have so damaged users’ trust in conflict footage that they no longer trust it. Even trusted news sources can’t tell real from fake anymore.

The researchers found anti-media sentiment among this deep skepticism about media veracity, which was “used to justify conspiratorial thinking and a distrust in reliable sources of news.”

Many X users commented, “None of the videos coming out of this war can be trusted. Over the next few years, media will use sophisticated deepfake software. If you think we have a problem now, wait until we see completely faked videos instead of their lies.

Another says, “This is a western media deepfake. Globalists control these journalists.”

The researchers conclude that we need better “deepfake literacy” to understand deepfakes and identify media tampering. The study also suggested that deepfake awareness may taint legitimate videos. So, news organizations and governments must be very careful when addressing manipulated media because they risk undermining trust.

“News coverage of deepfakes needs to focus on educating people on what they are, what their potential is, and both their current capabilities and how they will evolve in the coming years,” said University College Cork School of Applied Psychology lead study author John Twomey.

The study appears in PLOS ONE.

Tech Gadget Central Latest Tech News and Reviews

Tech Gadget Central Latest Tech News and Reviews