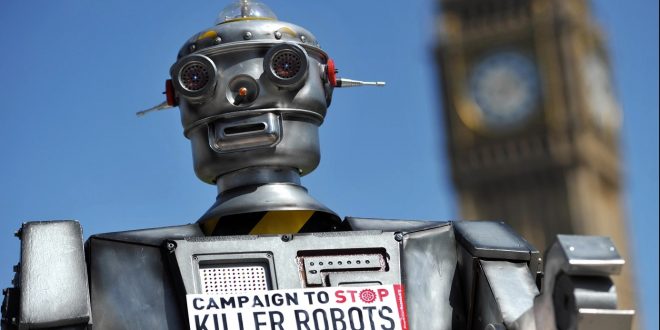

Looking for topics to discuss over the Thanksgiving dinner table that aren’t politics or sports? Let’s discuss killer robots now. Depending on how broadly you define “robot,” the idea has long since transposed from science fiction to reality. Asimov’s First Law of Robotics, which states that “A robot may not injure a human person” or “A robot may not, via inaction, enable a human being to come to harm,” was abandoned by military drones decades ago.

Due to the growing possibility of using killer robots in domestic law enforcement, the debate has recently flared up once more. Boston Dynamics, one of the most well-known robot manufacturers of the era, sparked some public policy concerns in 2019 when it showed video of their Spot robot being used in Massachusetts State Police training exercises.

The robots were not armed; rather, they were used in a test to see if they could keep cops safe in the event of a hostage or terrorist incident. However, the possibility of using robots in situations when people’s lives are immediately in danger was sufficient to trigger an investigation from the ACLU, which stated to TechCrunch:

Governmental organizations urgently need to be more open with the public about their plans to test and implement new technology. In the era of artificial intelligence, we also need statewide laws to safeguard civil liberties, human rights, and racial fairness.

Meanwhile, after seeing pictures of Spot being used to respond to a house burglary in the Bronx, the NYPD terminated a contract with Boston Dynamics last year.

Boston Dynamics, on the other hand, has been outspoken in its opposition to the use of their robots as weapons. Along with other top companies Agility, ANYbotics, Clearpath Robotics, and Open Robotics, it signed an open letter last month denouncing the decision. It says:

We think that putting weaponry to robots that are widely available to the general public, capable of going to previously inaccessible regions where people live and work, remotely or autonomously operated, creates new risks of injury and significant ethical concerns. These newly capable robots may be weaponized, which would undermine the enormous social benefits that this technology would otherwise have.

It was assumed that the letter addressed Ghost Robotics’ involvement with the American military in part. The Philadelphia company informed TechCrunch that it took an agnostic approach with regard to how the systems are used by its military clients after pictures of one of its own robotic dogs were posted on Twitter holding an autonomous rifle:

The payloads are not made by us. Will we endorse or publicize any of these armament systems? Most likely not. It’s challenging to respond to it. We don’t know what the military does with the items we sell to them because we don’t know. We won’t impose our preferences on how our government clients employ the robots.

Where they are sold is where we draw the line. We exclusively do business with American and allies’ governments. Even worse, we don’t offer our robots for sale to businesses in competitive markets. Our robots are frequently enquired about in China and Russia. We don’t ship there, not even for our business clients.

A legal dispute involving many patents is now ongoing between Boston Dynamics and Ghost Robotics.

Killer robots are once again causing fear, this time in San Francisco, according to the local police reporting website Mission Local. The website mentions terminology regarding killer robots in a policy proposal that the city’s Board of Supervisors will be considering next week. An inventory of the robots now in the San Francisco Police Department’s hands opens the “Law Enforcement Equipment Policy.”

There are 17 in all, and 12 of them are operational. They are not expressly made for killing; instead, they are mostly made for bomb detection and disposal.

The policy specifies that “the robots described in this section shall not be deployed outside of training and simulations, criminal apprehendings, critical occurrences, exigent circumstances, executing a warrant, or during suspicious device assessments.” The following sentence is even more alarming: “Robots will only be deployed as a deadly force option when risk of loss of life to members of the public or officers is immediate and outweighs any other force option available to SFPD.”

The phrase implies that the robots may be deployed to kill in order to protect cops’ or the public’s lives. In that situation, it might look innocent enough. It appears to at the very least meet the legal standard for “justified” deadly force. However, fresh issues are raised by what would seem to be a significant shift in policy.

To begin with, it has been done before to execute a suspect using a bomb-disposal robot. For what was thought to be the first time in American history, Dallas police officers carried out that exact action in July 2016. Police chief David Brown said at the time, “We saw no other option except to utilize our bomb robot and attach a device on its extension for it to detonate where the guy was.

Second, if a robot is employed in this way on purpose or by accident, it is simple to understand how the new precedent could be applied in a CYA scenario. Thirdly, and this is perhaps the most concerning, one could envision the phrasing referring to the acquisition of a future robotic system that was not solely created for the discovery and disposal of explosives.

The chair of the SF Board of Supervisors Rules Committee, Aaron Peskin, reportedly tried to substitute the more Asimov-friendly phrase, “Robots shall not be employed as a Use of Force against any person,” according to Mission Local. It appears that the SFPD modified it to reflect the current terminology and crossed out Peskin’s alteration.

Assembly Bill 481 is one reason why the topic of killer robots is once again being discussed in California. The bill, which Governor Gavin Newsom put into effect in September of last year, aims to increase the transparency of police activity. This covers a list of the military tools used by law enforcement.

The Lenco BearCat armored vehicle, flash bangs, and 15 submachine guns are included on the broader list that also contains the 17 robots mentioned in the San Francisco dossier.

Oakland Police announced last month that they will not be applying for permission to use armed remote robots. In a statement, the department stated:

The armed remote vehicle program is not being implemented by the Oakland Police Department (OPD). To consider all potential uses for the vehicle, OPD did participate in ad hoc committee discussions with the Oakland Police Commission and neighborhood residents. However, following more talks with the Chief and the Executive Team, the department made the decision it was no longer interested in investigating that specific alternative.

The declaration came after outcry from the public.

The first rule of Asimov is already out of the tube. The deadly robots have arrived. The second law, which states that “A robot must obey the directions provided to it by humans,” is still largely within our reach. The way that society’s robots act is up to them.

Tech Gadget Central Latest Tech News and Reviews

Tech Gadget Central Latest Tech News and Reviews