Chinese IT firms race to compete with Stable Diffusion and DALL-E 2, but obstacles remain.

Everyone is thrilled about the future of AI because to the enormous technological advancement that machine learning models have demonstrated in recent months, but they are also concerned about its unfavorable effects. The potential of ChatGPT to hold intelligent conversations has been the new focus in industries across the board after text-to-image solutions from Stability AI and OpenAI became the buzz of the town.

Entrepreneurs, researchers, and investors are seeking for methods to make a difference in the generative AI sector in China, where the tech community has historically carefully followed developments in the West. In order to draw in consumer and business clients, IT companies are developing solutions based on open source models. People are profiting from material produced by AI. Regulators have moved swiftly to outline appropriate uses for text, image, and video synthesis. Concerns about China’s ability to keep up with AI advancement are being raised in the meantime by U.S. tech restrictions.

Let’s look at how this explosive technology is developing in China as generative AI sweeps the globe by the end of 2022.

Chinese cuisine

Generative AI is becoming a hot topic, because to popular art production platforms like Stable Diffusion and DALL-E 2. Chinese IT firms have charmed the public with their identical products halfway over the world, adding a twist to fit the nation’s tastes and political environment.

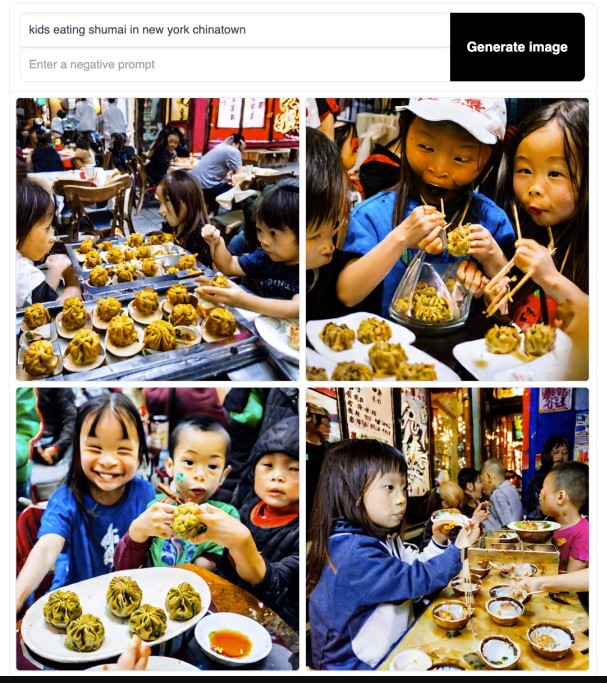

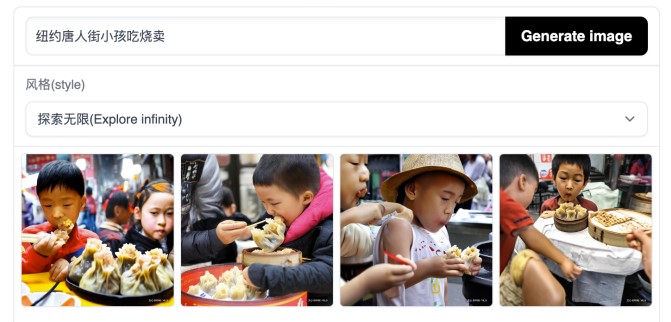

The 10-billion parameter ERNIE-ViLG model is run by Baidu, a search engine pioneer that has recently stepped up its game in autonomous driving. It was trained using a dataset of 145 million Chinese image-text pairs. How does it compare to the American version? The findings from Stable Diffusion’s response to the query “kids eating shumai in New York Chinatown” are shown below, along with the same prompt in Chinese () for ERNIE-ViLG.

I’d say the results are a tie as someone who grew up eating dim sum in China and Chinatowns. Both failed to order the proper shumai, a dim sum term for a sort of tender shrimp and pork dumpling with a yellow wrapper that is partially open. Although Stable Diffusion perfectly captures the feel of a Chinatown dim sum restaurant, its shumai is flawed (but I see where the machine is going). While ERNIE-ViLG does produce a certain variation of shumai, it is different from the Cantonese variety in that it is more frequently found in eastern China.

The fast test shows the challenge in capturing cultural nuances when the data sets utilized are inherently biased — presuming Stable Diffusion would have more data on the Chinese diaspora and ERNIE-ViLG probably is trained on a broader variety of shumai images that are rarer outside China.

Tencent’s Different Dimension Me, which can transform images of people into anime characters, is another popular Chinese tool. The bias of the AI generator is evident. Despite being targeted at Chinese consumers, it unexpectedly gained popularity in other anime-loving continents like South America. Users quickly noticed, however, that the platform’s failure to recognize black and plus-size people—groups that are conspicuously absent from Japanese anime—led to offensive AI-generated results.

Of course also clearly not having the model adjusted properly for darker-skinned folks, sigh

Anyway Different Dimension Me is the name, but sorry they already blocked / limit overseas users as couldn’t handle the traffic pic.twitter.com/cYi6rJwTaC

— Rui Ma 马睿 (@ruima) December 7, 2022

In addition to ERNIE-ViLG, another sizable Chinese text-to-image model is Taiyi, the creation of the IDEA research lab under the direction of renowned computer scientist Harry Shum, who also co-founded Microsoft Research Asia, the company’s largest research division outside of the United States. The open source AI model includes one billion parameters and was trained on 20 million filtered Chinese image-text pairs.

IDEA is one of a select group of organizations supported by local governments in recent years to work on cutting-edge technology, unlike Baidu and other profit-driven IT companies. As a result, the center probably has more freedom to do research without external pressure to achieve economic success. It’s an emerging group worth keeping an eye on, with a base in the Shenzhen innovation cluster and backing from one of China’s wealthiest cities.

Norms of AI

China’s generative AI technologies are influenced by local legislation in addition to the domestic data they use to train. Baidu’s text-to-image technology removes politically sensitive phrases, as MIT Technology Review noted. Given that internet filtering has long been a common practice in China, that is to be expected.

The government’s recent regulatory actions against “deep synthesis tech,” which is defined as “technology that combines deep learning, virtual reality, and other synthesis algorithms to generate text, images, audio, video, and virtual scenes,” are increasingly significant for the future of the young field.

Before utilizing generative AI apps, users in China are required to verify their names, just like with other online services like social media and games. The ability to link prompts to one’s real identity invariably has a constraining effect on user behavior.

On the plus side, these regulations may encourage more responsible usage of generative AI, which is already being misused to produce NSFW and sexist content in other places. For instance, the Chinese law expressly forbids the production and dissemination of false information produced by artificial intelligence. However, it is up to the service providers to determine how that will be carried out.

In an interview, Yoav Shoham, co-founder of AI21 Labs, an Israeli rival to OpenAI, said: “It’s intriguing that China is at the forefront of trying to govern [generative AI] as a country. There are several businesses that are restricting AI… Every nation that I am aware of is making an effort to govern AI or to ensure that the social or legal systems, specifically with regard to controlling the automatic generation of material, are keeping up with technology.

However, there isn’t yet agreement on how the rapidly evolving sector should be controlled. Shoham said, “I think it’s a field we’re all learning together.” “It needs to be a team effort. In addition to the government, including the sort of commercial and legal component of the regulation, it needs to involve technologists who truly understand the technology and what it does and doesn’t do, the public sector, social scientists, and individuals who are influenced by the technology.

AI monetization

Many people in China are using machine learning algorithms to earn money in a variety of ways as artists worry about being overtaken by sophisticated AI. They don’t belong to the technologically aware crowd. They are most likely opportunists or stay-at-home mothers seeking a second source of money. They understand that by making their prompts better, they may deceive AI into producing imaginative emojis or beautiful wallpapers, which they can then publish on social media to generate ad revenues or outright charge for downloads. Those who are extremely good also sell their suggestions to others who want to play the money game, or even train others to use them for a price.

Like the rest of the globe, some in China are utilizing AI in their professional work. For example, authors of light fiction, a genre that is shorter than novels and sometimes includes illustrations, can easily produce illustrations for their works at a low cost. Designing T-shirts, press-on nails, and prints for other consumer goods using AI is an exciting use case that has the potential to upend certain manufacturing industries. The manufacturing cycle is shortened and design expenses are reduced for manufacturers when they produce large batches of prototypes quickly.

It’s too soon to tell how generative AI is evolving in China and the West differently. However, business owners have made choices based on their initial observations. According to a few founders, firms are eager to carve out industry use cases because businesses and professionals are often willing to pay for AI because they see a clear return on investment. During the epidemic, it was revealed by Sequoia China-backed Surreal (later renamed to Movio) and Hillhouse-backed ZMO.ai that online retailers were finding it difficult to find overseas models since China kept its borders closed. The answer? Both businesses developed algorithms that produced fashion models of diverse sizes, hues, and races.

However, some business owners don’t think their AI-powered SaaS will experience the kind of rapid rise and skyrocketing valuation that its Western rivals, like Jasper and Stability AI, are. Since China’s enterprise customers are typically less willing to pay for SaaS than those in developed economies, many Chinese startups have expressed this issue to me over the years, which is why many of them begin to grow abroad.

Dog-eat-dog competition also exists in China’s SaaS market. “Building product-led software that doesn’t rely on human services to recruit or keep customers may be done reasonably well in the United States. However, in China, even if you have a fantastic product, your competitor may steal your source code overnight and hire dozens of inexpensive customer care agents to outperform you, according to a founder of a Chinese generative AI business who asked to remain anonymous.

Chinese businesses sometimes place a higher priority on immediate profits than long-term innovation, according to Shi Yi, founder and CEO of sales intelligence firm FlashCloud. Chinese tech companies “tend to be more focused on being adept at apps and making rapid money when it comes to talent development,” he said. An anonymous Shanghai-based investor claimed he was “a little unhappy that key discoveries in generative AI are all happening outside China this year.”

upcoming obstacles

Chinese tech companies could not have the greatest equipment even when they wish to invest in training massive neural networks. The U.S. government imposed export restrictions on high-end AI processors on China in September. While many Chinese AI startups are concentrated on the application side and do not require high-performance semiconductors that can handle oceans of data, using less powerful chips will result in longer computing times and higher costs for those conducting basic research, according to an enterprise software investor at a top Chinese venture capital firm who asked to remain anonymous. He claimed that the good news is that these penalties are incentivizing China to make long-term investments in cutting-edge technologies.

According to Dou Shen, executive vice president and head of the AI Cloud Group at Baidu, which calls itself a leader in China’s AI market, the impact of U.S. semiconductor sanctions on the company’s AI business is “minimal” both in the short and long terms. This is so that “a big chunk” of Baidu’s AI cloud business “does not rely too much on the highly advanced CPUs,” according to the report. Additionally, it has “already stockpiled enough in hand, actually, to support our business in the short term” in circumstances where it does need expensive chips.

The future, what about it? When considering the medium to long term, the executive boasted, “When we look at it at a mid- to longer-term, we actually have our own designed AI chip, so termed Kunlun.” The effectiveness of performing text and picture recognition tasks on our AI platform has been enhanced by 40% and the overall cost has been cut by 20% to 30% thanks to the use of our Kunlun chips in large language models.

If Kunlun and other domestic AI chips will provide China a competitive advantage in the generative AI race, only time will tell.

Yoav Shoham is a co-founder of AI21 Labs, as was clarified in an updated version of the report.

Tech Gadget Central Latest Tech News and Reviews

Tech Gadget Central Latest Tech News and Reviews