Google announced the launch of the first Beta for its “Privacy Sandbox” adtech stack proposal, which aims to iterate how ad tracking, targeting, and reporting is done so it appears less creepy for individual users while maintaining an interest-based, behavioral targeting capability on web users’ eyeballs. Google has started letting Android developers kick the tyres of its claimed reboot of ad-targeting.

As the adtech giant begins a gradual (but it claims global) rollout of the beta, which will “expand over time,” a “small percentage” of eligible Android 13 devices will be enrolled in the trial of the beta as of today. Developer advice on taking part in the beta can be found here.

For the trial, TechCrunch’s parent company Yahoo, the mobile game developer Rovio, the mobility company Wolt, the cross-platform game engine Unity, and the mobile marketing platforms AppsFlyer, InMobi Exchange, and Adjust are all advertising partners.

Google adds in a blog post that “if your device is selected for the Beta, you’ll receive an Android notification letting you know,” suggesting that Android users will automatically be opted in to the experimental, interest-based ad targeting (and will have to actively opt out if they don’t want their eyeballs to be test subjects).

Google confirmed that Android users in the European Economic Area, Switzerland, and the UK will be asked to voluntarily participate in the program — by way of opting in – when asked for confirmation on this opt in point.

This implies that users are being opted in elsewhere in the world and must manually opt out if they do not want to participate in these interest-based advertising tests.

Google focused on its desktop-based Chrome-browser and on phasing out third-party tracking cookies on the web when it first announced the so-called “Privacy Sandbox” proposal in 2019 to make ad-tracking less terrible for individual web users’ privacy (or, well, to make its business less of a target for the privacy backlash). However, it announced a year ago that it would bring the Sandbox approach to Android, and today it is allowing the first Android developers to test it out (and give feedback on it).

“The Privacy Sandbox Beta offers new APIs that are created with privacy in mind and don’t use identifiers that can track your online activity across different websites and mobile applications. In the blog post, Google’s Anthony Chavez explains how apps that choose to take part in the beta program can use these APIs to show you relevant ads and gauge their effectiveness.

The precise number of Android users who will be exposed to the test ad-targeting is unknown. or where these users will be located globally. Or what percentage will be opted in and required to choose themselves out via the settings if they do not wish to participate in the trial, as opposed to being asked for their affirmative consent.

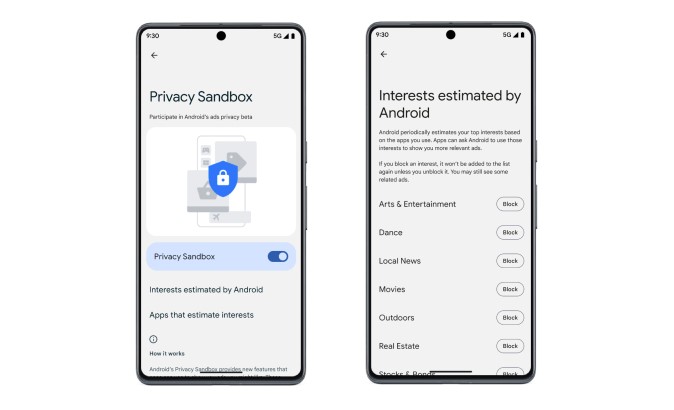

In his blog post, Chavez only makes it clear that Android users can “control” their “Beta participation” by visiting the Privacy Sandbox section of Settings. There, he claims, users will be able to “see and manage” the ad interests that participating apps may use to display “relevant ads,” as he refers to tracking-based marketing, to them.

He continues, “And if you change your mind about participating in the Beta, you can turn it off or back on in Settings. For example, you could see that Android has estimated that you’re interested in topics like Movies or Outdoors, and you can block any topics if they don’t fit your interests.”

Android users may have cause to doubt Google’s strategy with the implied interest-based ad targeting if they explore these settings and discover that they have been assigned “topics” that they do not hold.

Since Google has stated that the Topics taxonomy will be “human curated,” hopefully there won’t be any shocks worse than that. This is specifically to prevent the inclusion of “sensitive” topics as “estimated interests.”

However, it seems rather naive given how easily proxies can be identified for delicate subjects (a particular kind of TV show as a stand-in for political views, for example). Additionally, depending on how they use their device, users may want to think about whether their generated interests could be seen by someone else who has access to it.

These delicate privacy issues are not extensively covered in Google’s blog post.

Instead, the company chooses to criticize Apple’s App Tracking Transparency (ATT) feature, which mandates that third-party developers on iOS request users’ permission before engaging in in-app tracking. Chavez frames ATT as a “blunt” approach and provides a link to a study by a third-party tracker blocker that claims ATT only gives users a “false sense of privacy” by giving them a “false sense of security.”

Chavez claims in his blog post that Apple’s approach will result in increased user tracking via techniques like device fingerprinting while also hurting developers’ ability to make money from ads. It is clear that Google is attempting to position its technical reworking of ad-tracking as a more sophisticated tool. One that does not require binary decisions, such as asking individuals up front if they want to be tracked or not.

Instead, Google will hide options to turn off tracking in layered settings menus for the majority of Android users, further confusing the decision by implying that users could just reduce the amount of tracking they’re comfortable with, allowing behavioral targeting to continue (and spawning new estimated interests when users aren’t looking).

The Sandbox pitch Google has been developing over these years has coagulated and clotted around a claim that its evolved adtech stack will give users “more privacy” (as defined by Google — so definitely not total privacy) while letting the ad-tracking industry gravy train generate revenues but keeping it locked to Google’s “evolved” infrastructure; one which takes more of the tracking components in-house as tracking cookies get crushed (so, well, in more of a Google-dependent bind than ever).

Simply put, it’s a compromise offer for both parties that may ultimately not be acceptable to either end. If you will, a lose-lose situation. Google, however, obviously thinks the risk is worthwhile because if it is successful in rebranding tracking ads and in getting the Sandbox to be approved by privacy and competition regulators as well as the advertisers who complained to them, it will score the really big win of continuing to be the successful adtech middleman and bringing in the majority of the behavioral ad dollars.

Tech Gadget Central Latest Tech News and Reviews

Tech Gadget Central Latest Tech News and Reviews