Last year, Tulare Lake resurfaced in the San Joaquin Valley after being absent for 130 years. Currently, the elusive “phantom lake” has once again faded into obscurity, creating an uncertain future for the inhabitants and agricultural workers of California’s Central Valley.

Tulare Lake was formerly the largest lake to the west of the Mississippi River, containing a substantial volume of water spanning a length of 160 kilometers (100 miles) and a width of 48 kilometers (30 miles).

Referred to as Pa’ashi by the Indigenous Tachi Yokut tribe, this location has been utilized as a customary area for hunting and fishing for many centuries. In the 19th century, the state of California underwent significant transformations when it engaged in a series of aggressive acquisitions of land and subsequently transferred ownership of the region to private individuals during the 1850s and 1860s.

The lake was depleted of water and transformed into cultivable farmland. By the 1890s, it had completely vanished. Tulare Lake resurfaced intermittently a few times in the last century, earning a reputation as a “ghost lake,” but it was generally regarded as a concluded matter.

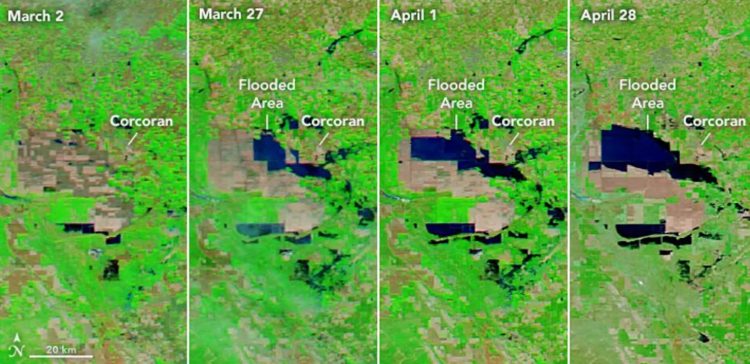

Subsequently, in the beginning of spring 2023, it resurfaced yet again following weather phenomena in southern California.The Sierra Nevada mountains, which experienced numerous snowstorms during the winter of 2023, contributed to a significant influx of water into the San Joaquin Valley, which supplies the body of water.

The revival of it was both a boon and a bane. Although the floodwaters caused significant damage to agricultural land and property, they also resulted in the resurgence of indigenous fauna. Additionally, the Tachi Yokut tribe successfully reclaimed their ancestral lake.

The majority of the news reports during this period described the flooding as catastrophic. Vivian Underhill, a former postdoctoral research fellow at Northeastern University’s Social Science and Environmental Health Research Institute, emphasized that while the personal and property losses resulting from the event should not be ignored, it is important to acknowledge that it was not just a period of loss but also a period of recovery and renewal.

The resurgence of the lake has proven to be an immensely potent and profound encounter for the Tachi Yokuts, evoking strong spiritual sentiments. Ceremonies have been taking place on the lakeside. According to Underhill, they have regained the ability to engage in their customary hunting and fishing activities.

In early February, Underhill forecasted that the lake would persist for a minimum of two years. However, within a few weeks, it had nearly vanished.

“The lake no longer exists.” “There is some moist soil, but it is not significant,” stated Doug Verboon, a Kings County supervisor and farmer, in an interview with the San Francisco Chronicle.

Although the lake is currently disappearing, researchers at Northeastern University predict that it will likely reappear again in the future due to ongoing climate change, which will result in more extreme weather in the Sierra Nevada mountains and increased flooding in the downstream area.

“According to Underhill, this landscape has historically consisted of lakes and wetlands, and our current practice of irrigated agriculture is a relatively short period of time in comparison to the overall geological history,” Underhill clarified.

“This event did not meet the criteria to be classified as a flood.” This is the reappearance of a lake.

Tech Gadget Central Latest Tech News and Reviews

Tech Gadget Central Latest Tech News and Reviews