Meta, formerly Facebook, has been ordered to stop exporting EU user data to the U.S.

The European Data Protection Board (EDPB) fined Meta €1.2 billion (close to $1.3 billion) today, the largest GDPR fine ever. Amazon was fined $887 million in 2021 for misusing customer data for ad targeting.

Meta was fined for violating the pan-EU regulation on data transfers to third countries (the US) without adequate protections.

U.S. surveillance violates EU privacy rights, according to EU judges.

Andrea Jelinek, EDPB chair, stated:

The EDPB found that Meta IE’s [Ireland’s] infringement is very serious since it concerns transfers that are systematic, repetitive and continuous. Facebook has millions of users in Europe, so the volume of personal data transferred is massive. The unprecedented fine is a strong signal to organisations that serious infringements have far-reaching consequences.

The Irish Data Protection Commission (DPC), which implements the EDPB’s binding decision, had not commented as of writing. Its final decision is here.

Meta quickly posted on its blog that it will appeal the suspension order, calling the fine “unjustified and unnecessary”. Nick Clegg, president, global affairs, and Jennifer Newstead, chief legal officer, wrote:

We are appealing these decisions and will immediately seek a stay with the courts who can pause the implementation deadlines, given the harm that these orders would cause, including to the millions of people who use Facebook every day.

The adtech giant warned investors in April that an EU data flow suspension would threaten 10% of its global ad revenue.

Meta spokesman Matthew Pollard declined to provide “extra guidance” on its suspension preparations before the decision. Instead, he pointed to an earlier statement in which the company claimed the case involves a “historic conflict of EU and US law” that EU and US lawmakers working on a new transatlantic data transfer arrangement are resolving. Pollard’s rebooted transatlantic data framework is still unimplemented.

In its conclusion, the DPC writes: “This decision will bind Meta Ireland only. It is clear, however, that the analysis in this Decision exposes a situation whereby any internet platform falling within the definition of an electronic communications service provider subject to the FISA 702 PRISM program may equally fall foul of the requirements of Chapter V GDPR and the EU Charter of Fundamental Rights regarding their transfers of personal data to the USA—so pressure is likely to be amplified on lawmakers on both sides of the Atlantic to get the issue

Max Schrems, a vocal critic of Meta’s lead data protection regulator in the EU, filed a complaint against Facebook’s Irish subsidiary almost a decade ago, accusing the Irish privacy regulator of taking an intentionally long and winding path to frustrate effective enforcement of the bloc’s rulebook.

Schrems claims that only the U.S. can fix the EU-U.S. data flow doom loop by reforming its surveillance practices.

“We are happy to see this decision after ten years of litigation,” he said of today’s order through his privacy rights non-profit, Noyb. Meta intentionally broke the law for ten years, so the fine could have been much higher. Meta will have to fundamentally restructure its systems unless US surveillance laws are fixed.”

The DPC, which oversees GDPR compliance for multiple tech giants with regional headquarters in Ireland, rejects criticism that its processes slow enforcement, arguing that they are necessary to perform due diligence on complex cross-border cases. It also blames other supervisory authorities that object to its draft decisions for delays.

However, DPC draft decisions against big tech have resulted in stronger enforcement via the GDPR’s cooperation mechanism, as in Meta and Twitter’s cases.

This suggests that the Irish regulator routinely under-enforces the GDPR on the most powerful digital platforms, which delays enforcement and makes the regulation less efficient. In the Facebook data flows case, the DPC’s draft decision was objected to last August, so it took nine months to reach a final decision and suspension order. If you delay enforcement long enough, the political goalposts may move, and enforcement may never be needed. While convenient for data-mining tech giants like Meta, it violates citizens’ rights.

As noted above, the DPC is implementing a binding decision taken by the EDPB last month to settle ongoing disagreement over Ireland’s draft decision, so much of what’s being ordered on Meta today comes from the bloc’s supervisory body for privacy regulators.

The Board instructed the DPC to include a financial penalty in its draft, writing:

Given the seriousness of the infringement, the EDPB found that the starting point for calculation of the fine should be between 20% and 100% of the applicable legal maximum. The EDPB also instructed the IE DPA to order Meta IE to bring processing operations into compliance with Chapter V GDPR, by ceasing the unlawful processing, including storage, in the U.S. of personal data of European users transferred in violation of the GDPR, within 6 months after notification of the IE SA’s final decision.

Meta can be fined 4% of its global annual turnover under the GDPR. It could have been fined over $4 billion since its full-year turnover last year was $116.61 billion. The Irish regulator fined Meta less than it could have, but still more than it wanted.

Today, Schrems again accused the DPC of undermining GDPR enforcement. We sued the Irish DPC for ten years to get this result. Three DPC procedures risked millions in procedural costs. The Irish regulator tried everything to avoid this decision but was repeatedly overruled by European courts and institutions. “It’s absurd that Ireland, the EU Member State that did everything to avoid this fine, will get the record fine,” he said.

Facebook’s European future

Nothing immediately. The service will continue to work during the six-month transition period before data flows are suspended. Meta has five months to stop transferring personal data to the U.S. and six months to stop unlawfully processing and/or storing European user data it transferred without a legal basis.

Meta also plans to appeal and request a stay.

Schrems has suggested that Facebook will need to federate its infrastructure to provide a service to European users without exporting their data to the U.S. However, the transition period in today’s decision should give Meta enough time to adopt the transatlantic data transfer deal, allowing it to avoid suspending EU-U.S. data flows.

Earlier reports suggested the European Commission could adopt the new EU-U.S. data deal in July, but it has declined to provide a date because multiple stakeholders are involved.

Meta gets a new escape hatch to avoid suspending Facebook’s service in the EU and can keep using this high-level mechanism as long as it exists.

If that’s how the next chapter of this torturous complaint saga plays out, a case against Facebook’s illegal data transfers that dates back almost ten years will again be left twisting in the wind, raising questions about whether Europeans can exercise their GDPR legal rights. (And whether deep-pocketed tech giants with well-paid lawyers and lobbyists can be regulated at all?)

Schrems gives the EU-U.S. data transfer deal a slim chance of surviving legal challenges.

Meta and other U.S. companies that export data for processing abroad may soon be back in this doomsday loop.

Schrems said Meta plans to use the new deal for transfers going forward, but it may not be permanent. I think the new deal has a 10% chance of surviving the CJEU. Meta may have to keep EU data in the EU unless US surveillance laws change.

Meta may also have to delete historical data transfers since there was no legal basis for them.

Any new transatlantic mechanism should only affect future data flows, not past exports. Meta may have ongoing issues. The adtech giant may have trouble complying with an order to selectively delete Europeans’ data due to leaks of internal documents.

Meta claims in its blog post that the DPC confirmed “in its decision” that Meta will not be required to delete EU data subjects’ data “once the underlying conflict of law has been resolved”.

Meta pointed us to the following section of the decision (highlighting the bold text) when it cites data deletion as an example:

Accordingly, and as directed by the EDPB further to the Article 65 Decision, I have included, in Section 10, below, an order requiring Meta Ireland to bring processing operations into 149 compliance with Chapter V GDPR, by ceasing the unlawful processing, including storage, in the US of personal data of EEA users transferred in violation of the GDPR, within the period of 6 (six) months from the date on which this Decision is notified to Meta Ireland (“the Cessation Order”). I note, in this regard, that neither the CSAs [concerned supervisory authorities] (by way of the Deletion or Return Objections or otherwise) nor the EDPB expressed disagreement with my view, set out at paragraph 9.46 above, that “new measures, not currently in operation, may yet be capable of being developed and implemented by Meta Ireland and/or Meta US to compensate for the deficiencies identified herein”. While that view was expressed in the context of the suspension order that was proposed by the DPC in the Draft Decision (and which is reflected in Section 10, below), it applies equally to the Cessation Order. Accordingly, and for the sake of clarity and legal certainty, the orders specified in Section 10, below, will remain effective unless and until the matters giving rise to the finding of infringement of Article 46(1) GDPR have been resolved, including by way of new measures, not currently in operation, such as the possible future adoption of a relevant adequacy decision by the European Commission pursuant to Article 45 GDPR.

We asked the DPC if it had assured Meta of historical data deletion. Graham Doyle, deputy commissioner, advised asking Meta. “My understanding is that the EDPB and DPC decisions don’t reference deletion; they reference bringing processing into compliance—maybe that’s what Meta is referring to, but I don’t know without asking them,” he said, without directly responding.

Helen Dixon, the DPC’s data protection commissioner, wrote that “bulk return and/or deletion of all transferred data from an identified point in time would be excessive” in her draft complaint decision.

“The EDPB Binding Decision requires ‘the imposition of an order to Meta IE to bring processing operations into compliance with Chapter V GDPR by ceasing the unlawful processing, including storage, in the US of personal data of EEA users transferred in violation of the GDPR’,” an EDPB spokeswoman said of data deletion. The binding decision does not state whether deletion is required.”

“It would be for the Irish DPA to decide on reconsidering both orders (one on future transfers, one on data transferred in the past),” she said.

In a press conference earlier today, a Commission spokesman said, “This decision implements the decision of the European community to protect data — a decision by the European Data Protection Board. Meta must resolve these transfers, according to Irish authorities.

The spokesman then addressed EU-U.S. data transfers “generally,” stating that the Commission expects a new transatlantic data adequacy deal to be “fully functional by the summer”.

“This will guarantee stability and legal certainty, both sought by businesses, and will also guarantee strict protection of the private lives of citizens,” he said. “We expect it will also be challenged at some point. However, we are implementing the court-ordered safeguards.

A Commission spokesman called the question a “legally complex question” and said, “We’ll have to see.”

We arrived, how?

How indeed.

Schrems was acting after NSA whistleblower Edward Snowden revealed in 2013 that U.S. government surveillance programs were collecting user data from social media websites (aka PRISM), among other revelations about mass surveillance.

European law protects personal data, which Schrems believed was at risk due to U.S. laws prioritizing national security and giving intelligence agencies broad powers to snoop on Internet users.

His initial complaints targeted several tech giants for alleged PRISM data collection compliance. In July 2013, Ireland’s data protection authority dismissed two complaints against Apple and Facebook, arguing that their Safe Harbor registration eliminated surveillance concerns.

Schrems appealed the regulator’s decision to the Irish High Court, which referred the case to the Court of Justice of the EU (CJEU), which struck down Safe Harbor in October 2015 after finding it unsafe and lacking essential equivalence of the EU’s data protection regime for data exports to the U.S. Schrems, I was that ruling. (Stay for Schrems II.)

Schrems refiled his complaint against Facebook in Ireland two months after the CJEU’s bombshell, asking the data protection authority to suspend Facebook’s EU-U.S. data flows due to the “very clear” judgment on U.S. government surveillance programs.

Since Safe Harbor’s demise affected thousands of businesses, EU and U.S. lawmakers scrambled to negotiate a new data transfer deal. By July 2016, the EU-U.S. Privacy Shield, the replacement adequacy deal, had been signed.

As a rush job, Privacy Shield was plagued by concerns that it was just a bandage over a legal schism. Schrems called it “lipstick on a pig,” as usual. To sum up, the CJEU agreed and shattered the Shield in July 2020 in another landmark ruling on U.S. surveillance law versus EU privacy rights.

Schrems had not directly challenged Privacy Shield. He instead requested that the Irish DPA suspend Facebook’s use of standard contractual contracts (SCCs), a longer-standing data transfer mechanism.

The Irish watchdog refused again. Instead, it said “hold my beer” and went to court to challenge the legality of SCCs, claiming that the entire mechanism was unsafe.

The DPA’s legal challenge to SCCs halted Schrems’ complaint against Facebook’s data flows while the data transfer mechanism was examined. However, the Irish High Court referred Privacy Shield to the CJEU in April 2018 to question its legitimacy. Next, you know: Two years later, the bloc’s top judges ruled that this second claim of adequacy was deficient, rendering the mechanism inoperable. Privacy Shield dies. (Schrems II)

But Facebook used SCCs, not Privacy Shield, to authorize these data transfers! The CJEU did not invalidate SCCs, but the judges made it clear that when they are used to export data to a “third country” (like the U.S.), EU data protection authorities have a duty to monitor and intervene when they suspect data is not adequately protected in the risky location. The CJEU made enforcement clear. Add to that the court’s invalidation of Privacy Shield due to U.S. surveillance practices, and Facebook’s data collection country was clearly unsafe.

Facebook’s business model relies on access to user data to track and profile web users to target them with behavioral ads, so it couldn’t apply extra safeguards like end-to-end encryption to protect Europeans’ data exported to the U.S.

With U.S. data adequacy gone and Facebook’s alternative mechanism under CJEU scrutiny, the Irish DPA sent Facebook’s parent, Meta, a preliminary order to suspend data flows in September 2020.

Meta obtained a stay and challenged the order in court, triggering a new round of legal battles. However, the Irish regulator made another strange decision, opening a new procedure while pausing Schrems’ long-standing complaint.

Schrems complained, suspecting new delaying tactics, and obtained a judicial review of the DPA’s procedures, which led the Irish DPA to quickly finalize his complaint in January 2021.

In May, the Irish courts dismissed Meta’s legal challenge to the DPC, lifting the stay on its decision-making process. Ireland had no more excuses to decide Schrems’ complaint. This put the saga back on GDPR enforcement tracks, with the DPC investigating for a year and reaching a revised preliminary decision in February 2022, which it then sent to fellow EU DPAs for review.

August 2022 saw objections to its draft decision. The European Data Protection Board (EDPB) made a binding decision in April 2023 after EU authorities failed to agree.

The EDPB’s binding decision gave the Irish regulator one month to make a final decision. Dublin isn’t responsible for today’s decisions.

Meta-escape: EU-U.S. Data Privacy Framework

Still more. As mentioned above, another important detail may affect Meta’s data flows in the near future and lead to a Schrems III: EU and U.S. lawmakers have been meeting for years to address the CJEU’s concerns and restore U.S. adequacy after Privacy Shield was torpedoed.

At the time of writing, work to implement this replacement data transfer deal is still underway, with adoption expected in the summer, but it has already proven much more difficult than last time.

The EU-U.S. Data Privacy Framework (DPF) was announced in March 2022, followed by an executive order from U.S. President Joe Biden in October and a draft agreement from the Commission in December. Meta doesn’t have a high-level framework yet because the EU’s adoption process hasn’t finished.

Meta will likely join the DPF if and when the EU adopts it to certify its EU-U.S. data flows. This is one way Facebook can delay the suspension order until its legal appeal is resolved. “We are pleased that the DPC also confirmed in its decision that there will be no suspension of the transfers or other action required of Meta, such as a requirement to delete EU data subjects’ data once the underlying conflict of law has been resolved,” Meta wrote in its blog post today. This means that if the DPF takes effect before the implementation deadlines, our services can continue as usual without disruption or impact on users.

But Schrems or other digital rights groups will likely challenge the DPF’s legality. If that happens, the CJEU may again find a lack of safeguards since we have not seen substantial reforms of U.S. surveillance law since they last checked in and data protection experts have raised concerns about the reworked proposal.

The Commission claims the two sides have worked hard to address the CJEU’s concerns, including new language they say will limit U.S. surveillance agencies’ activity to “necessity and proportionality,” enhanced oversight, and a “Data Protection Review Court” for individual redress.

However, data protection experts question whether U.S. spooks will follow EU law’s definition of necessity and proportionality, especially since bulk collection remains possible under the framework. They also argued that since the body being framed as a court will make secret decisions, redress for individuals will be difficult.

As reported, Schrems remains skeptical. In a recent briefing ahead of the GDPR’s five-year anniversary, he told journalists, “We don’t think the current framework is going to work.” “We think that’s going back to the Court of Justice and will be another element that just generates a lot of tension between the different layers [of enforcement].” He also said the executive order Biden signed for the new arrangement is “pretty much identical” to President Obama’s presidential policy directive, which the Court of Justice reviewed when determining Privacy Shield’s legality.

“The new technical order has new elements and improvements. Most of the “new” stuff in press releases and public debate is actually old. However, he claimed “So we oftentimes don’t really understand how that should change much, but we’ll go back to the courts in the next year or two, and we’ll probably get to the Court of Justice and have a third decision that will either tell us that everything is not cool and wonderful and we can move on or that we are just going to be stuck in that for longer.”

If you listen to the high-level mood music, the framework contains significant legal schism fixes. In a few years, the CJEU will decide if that’s true.

That means EU-U.S. adequacy could fail again soon. That would restart Facebook’s data transfer issue due to U.S. surveillance and national security policies that violate European privacy and data protection laws.

EU adequacy of essential equivalence to the bloc’s data protection regime is a hard stop where fudges won’t last. DPF survival calculations are further complicated by the possibility of Donald Trump becoming president again in 2024. That’s for later.

Irish GDPR enforcement “bottleneck”

Schrems’ near-decade-long battle for a decision on his complaint is a prime example of delayed data protection enforcement. If you ignore all the complaints where the regulator did nothing, it may be a record of how long someone waited.

However, the Irish DPC’s GDPR enforcement record is under greater scrutiny than just this data flow saga. (Which even Schrems seems to want gone.)

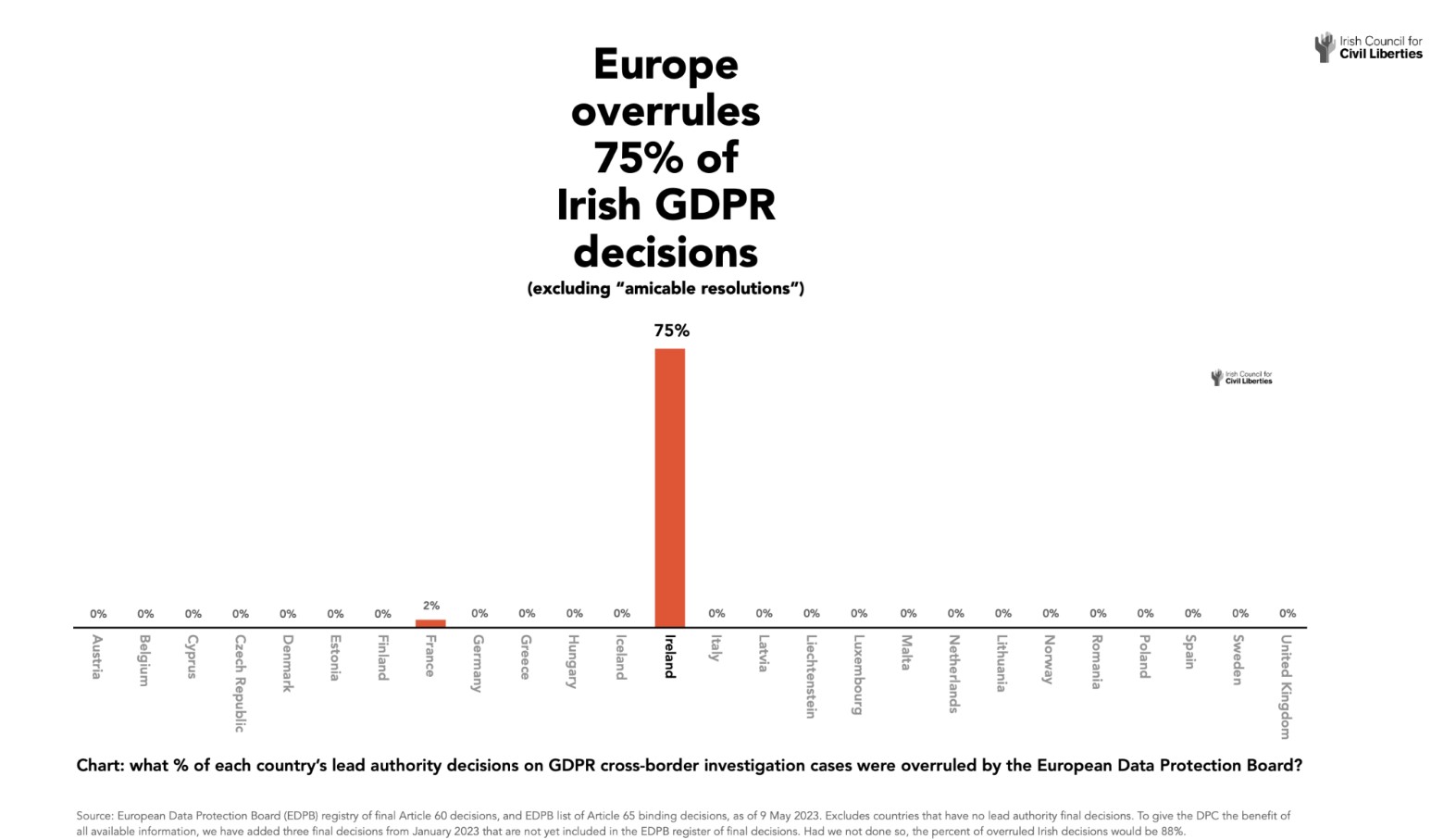

“Europe’s failure to enforce the GDPR exposes everyone to acute hazards in the digital age, and fingering Ireland’s DPA as a leading cause of enforcement failure against Big Tech,” the Irish Council for Civil Liberties (ICCL) warned earlier this month in its five-year GDPR analysis.

The ICCL blames Ireland’s DPC.

“Ireland continues to be the bottleneck of enforcement: it delivers few draft decisions on major cross-border cases, and when it does, other European enforcers routinely vote by majority to force it to take tougher enforcement action,” the report states. “Uniquely, 75% of Ireland’s GDPR investigation decisions in major EU cases were overruled by the majority vote of its European counterparts at the EDPB, who demand tougher enforcement.”

The ICCL also notes that 87% of cross-border GDPR complaints to Ireland involve Google, Meta (Facebook, Instagram, and WhatsApp), Apple, TikTok, and Microsoft. However, many tech giant complaints are never fully investigated, depriving complainants of their rights.

According to the oversight body’s statistics, the Irish DPC resolves 83% of cross-border complaints with “amicable resolution,” which “contravenes European Data Protection Board guidelines.”

The DPC declined to comment.

“The Commission’s forthcoming proposal to improve how DPAs cooperate may help, but much more is required to fix GDPR enforcement,” the ICCL warned. Didier Reynders is responsible for this crisis. He must act.”

Today’s final decision on Facebook’s data flows flopping out of Ireland, after almost a decade of procedural dilly-dallying—which, let’s not forget, has claimed the scalps of not one but two high-level EU-U.S. data deals—won’t do anything to quell criticism of Ireland as a GDPR enforcement bottleneck (regardless of helpful press leaks last week ahead of today’s Facebook data flows decision (and indeed today!), seeking to frame a positive narrative for

Indeed, the lasting legacy of the Facebook data flows saga and other painstakingly extracted DPC under-enforcements against Big Tech’s systematic privacy abuses is already writ large in the Commission’s centralized oversight role of Big Tech for the Digital Services Act and Digital Markets Act—a development that recognizes the importance of regulating platform power for securing the future of the European project.

However, Ireland’s data protection authority cannot handle all GDPR enforcement issues.

As you might expect with a decentralized oversight structure that factors in linguistic and cultural differences across 27 Member States and varying opinions on how best to approach oversight atop big (and very personal) concepts like privacy, which may mean very different things to different people, a patchwork of problems frustrates effective enforcement across the bloc.

Schrems’ privacy rights not-for-profit, Noyb, has been compiling information on this patchwork of GDPR enforcement issues, which include under-resourcing of smaller agencies and a general lack of in-house expertise to deal with digital issues; transparency problems and information blackholes for complainants; cooperation issues and legal barriers frustrating cross-border complaints; and all sorts of “creative” interpretations of complaints “handling”—meaning

“In many cases, you have a right to complain, but the chances are that this will not help you or fix your problem. If we have a fundamental right to privacy and pump millions of euros into these authorities, that’s a problem. “And the answer we have to give to people is to say you can give it a try but very likely it’s not going to help you—and that is my biggest worry after five years of the GDPR that unfortunately that’s still the answer we have to give people,” says Schrems.

However, Ireland’s role in GDPR enforcement on Big Tech, which affects web users’ rights, affects hundreds of millions of European consumers. Dublin deserves scrutiny.

Tech Gadget Central Latest Tech News and Reviews

Tech Gadget Central Latest Tech News and Reviews