What will become of the 15,000 vibrant electric scooters that are currently littering Paris’ streets? Their future may take a dramatic turn on March 23 as the French capital decides whether or not to renew licenses for the three scooter businesses that are currently doing business there.

The three businesses that have held such licenses since 2020—Dott, Tier, and the Uber-affiliated Lime—will not be the only ones affected by this. The choice will serve as a model for the several towns around the globe that have already permitted scooters on their streets. If things don’t work out, a bad decision in Paris might have a deterrent effect for micromobility firms around the world.

Paris has set the pace in the competition for electric scooters. Scooters in Paris provided a refutation to the claims that they were overhyped, over-capitalized by unimaginative VCs, and a flash in the pan. Paris was one of the first cities to approve their use in open city environments, and city residents (and visitors) took to them as a convenient way to navigate around halting traffic and crowded public transportation.

“Everyone should pay attention to this. Paris is significant in terms of business scale since it is the largest city in the world from a commercial perspective, according to Matthieu Faure, director of marketing and communications at Dott. “Paris is significant from a symbolic standpoint as well,” said the speaker.

When the city’s Deputy Mayors David Belliard and Emmanuel Grégoire asked the three mobility operators to meet in September 2022, things started to look iffy. They claimed that in terms of safety and urban clutter, Dott, Lime, and Tier weren’t doing enough. However, the city of Paris had already expressed dissatisfaction with these services.

A dozen distinct scooter businesses initially launched their fleets in Paris as a result of the lack of suitable regulations from the beginning. These startups included Bird, Bolt, Bolt by Usain Bolt (oui, deux Bolts), Circ, Dott, Hive, Jump, Lime, Tier, Voi, Ufo, and Wind.

This ultimately resulted in the tender procedure and a new set of regulations, including a 20 km/h maximum speed restriction and certain designated parking places.

Tragically, a pedestrian was murdered in a scooter accident in 2021. More limitations on scooter services resulted from that. In particular locations, such as pedestrian streets, public squares, and regions without cars, scooter businesses agreed to create hundreds of slow zones with a 10 km/h speed restriction. The mayor of Paris once contemplated making the entire city a slow zone but abandoned the idea.

The issue of climate change is another; the question is whether it is a strong enough argument. Promoters of scooters frequently claim that they are a sustainable mode of transportation. Scooters aren’t necessarily helping with environmental aims in some metropolitan areas, TechCrunch’s Rebecca Bellan has noted. In Paris, this is the situation.

When residents of Paris need to get from A to B, they have a ton of options thanks to the city’s extraordinarily dense population, effective subway system, and subsidised bike-sharing program with more than 400,000 participants. When compared to the metro, which is undoubtedly a greener method of transportation than electric scooters, many people who use scooters instead of them would have used their moped or called an Uber.

However, electric scooters have been widely adopted by both visitors and Parisians.

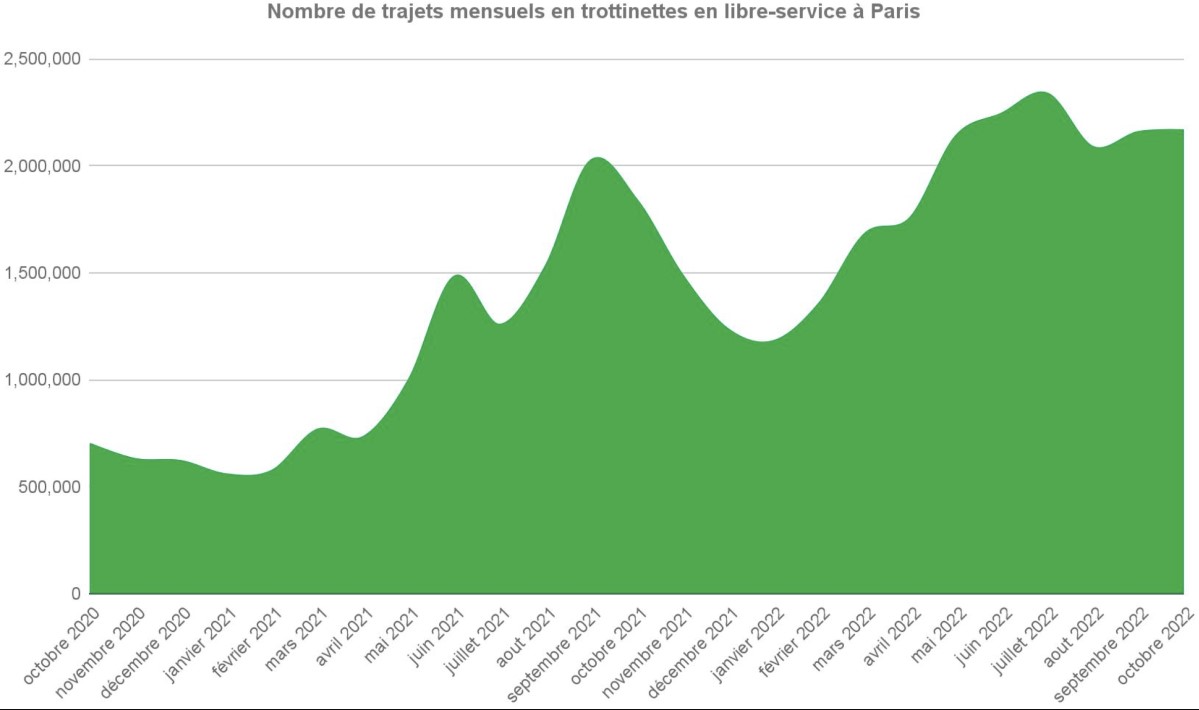

Dott, Lime, and Tier logged more over 2 million rides in October 2022. 85% of the 400,000 users in Paris who are split throughout the three services reside there.

There are approximately 15,000 scooters on Paris’s streets because each operator has a strict cap of 5,000 scooters. In 33 European cities, there are around 300,000 shared scooters, according to Fluctuo.

However, each scooter is used extremely frequently—multiple times each day—in Paris. The total number of scooter rides in Paris per month is shown in the following graph:

These measurements’ promise has sparked enormous valuations and fundraising rounds. One of the businesses that popularized the idea of free-floating scooters, Lime, has raised $1.5 billion to far, according to Crunchbase. While Tier took roughly $650 million, Dott was able to secure $210 million.

It’s true that for the majority of the past year, funding for these startups has largely been quiet. This is partially due to the fact that Bird, the most well-known of these companies and one that is notable for not being based in Paris but rather trading on the NYSE, has completely ran out of power. (Bird announced last week that it had raised $32 million through convertible notes and personal investments from its founder and chairman Travis VanderZanden and CEO Shane Torchiana. The company’s market cap is currently less than $86 million, down from more than $2 billion when it went public in March 2021. The funding arrived concurrently with Bird’s acquisition of the previously spun-off Bird Canada and other actions taken to try to strengthen its financial position.)

Following the meeting in September 2022, the three active scooter businesses (Lime, Dott, and Tier) received a message from the city: they shouldn’t assume that their licenses will be renewed in 2023. Their top concern became demonstrating that they are respectable businesses in their major metropolis because the general market environment was not favorable.

The three operators came up with a list of 11 suggestions in October 2022 to increase safety and integrate public spaces, ranging from prohibiting users who violate traffic rules to utilizing camera-based sidewalk detection systems.

Even some of those things have begun to be implemented by Dott, Lime, and Tier. They required individuals to upload a photo of their ID and established an age verification system. Similar to this, each scooter now has a license plate. In this manner, if there are two scooter riders, the police can record the license plate number and the current time. The manufacturers of scooters can then determine who was operating a particular scooter at a given moment.

“We chose to proactively roll out two of these in December, specifically with regard to ID verification and license plates. Over 160,000 IDs have been validated and examined, and after 30 days, all shared e-scooters in Paris now have license plates, according to Tier’s Erwann Le Page, director of public policy for Western Europe.

What took place after that? Nothing took place.

The silent treatment in negotiations

The restriction of scooters has divided the city of Paris. One of the most outspoken critics has been Deputy Mayor David Belliard. He frequently says that scooters ought to be outlawed, and his statements are taken seriously because he is in charge of transportation, among other things.

However, the fact that he is utilizing media appearances to argue that scooters need to be outlawed shows that not all members of the city council share his opinion.

Dott’s Matthieu Faure stated, “It’s just his personal stance; he’s against shared scooters. “We’re not exactly sure why. He offers no logical justification.

What specifically does Paris Mayor Anne Hidalgo think about scooters? Nobody can be certain.

The City Council is yet to announce a decision. According to a Lime representative, “to date, the City has not responded to any of the meeting requests or letters submitted by Lime or the two other operators.

“Paris has not yet responded to our inquiries. Erwann Le Page of Tier further stated, “Our contract expires on March 23rd.

We have reached out to the city of Paris for comment, and if we hear back, we’ll update the story.

I believe Anne Hidalgo will finally have to make the decision on the renewal of scooter licenses. The rest of the information you hear on this subject is noise.

Additionally, there is now no necessity to contact scooter manufacturers. Due to the Paris mayor’s silence, scooter companies have already improved the safety of their services.

In other words, the best course of action to elicit changes from operators at this time is to say nothing.

reducing Paris’s reliance on scooters

In contrast to the early days of shared scooters, most micromobility businesses now use full-time staff to transport, repair, and replace vehicles as well as swap out batteries.

800 individuals are currently employed by Dott, Lime, and Tier in Paris. Alongside the three operators, another 200 individuals indirectly work. Particularly, a subcontractor firm works with all three businesses and patrols Paris’s streets.

And this model has shown to be effective. Dott claims that, when all fixed and variable costs linked with its Paris operations, such as amortization and depreciation of vehicles, are taken into consideration, it is currently profitable in Paris (EBIT profitable).

Even though Dott, Lime, and Tier are presently operational in other places, a major portion of their earnings still comes from Paris. They probably made the decision to start bike-sharing programs with free-floating electric bikes for that reason.

A Lime representative informed me, “We are now running 7,000 [bikes] in Paris and we aim to continue doing so.” Similar to Tier, Dott oversees 2,500 electric bikes while Dott has a fleet of 3,500 bicycles.

Free-floating bikes were not subject to a tendering procedure this time, but operators were still required to sign a contract with the city of Paris. Moreover, they pay a license cost.

The addition of electric bikes is a wise decision given the similarities between scooters and bikes. For instance, Lime utilizes the same batteries for both its scooters and bikes, making it possible for the operations staff to swap out batteries while driving through Paris’s streets.

However, it seems evident that Dott, Lime, and Tier still intend to continue selling scooters after March 23. A handful of Dott, Lime, and Tier employees demonstrated in front of the municipal hall on Wednesday. They requested a meeting with city representatives in order to clarify things.

Their requests were once more met with silence. The looming deadline forces the mayor of Paris to decide sooner rather than later, even if the city of Paris doesn’t seem to care about media coverage of the license renewal. And a lot of micromobility businesses and municipal governments are focusing on what the solution will be.

Tech Gadget Central Latest Tech News and Reviews

Tech Gadget Central Latest Tech News and Reviews