Observations have shown that tidal forces are exerting pressure on the Thwaites Glacier, causing relatively warm water to flow beneath it. As a result, a significantly larger portion of the glacier’s ice is being exposed to the effects of warming. The observations suggest that a devastating increase in sea levels may occur earlier than most individuals are currently anticipating.

Elevated temperatures are causing an increase in sea levels through the expansion of existing ocean water and the melting of alpine glaciers and the Greenland ice sheet. All of these factors are highly likely to escalate, posing a significant threat to coastal cities across the globe. However, the rate at which Antarctic ice will melt remains highly uncertain, which could significantly increase the existing estimates for flooding risks. Although Antarctica is incredibly large, there is one specific glacier, known as the Thwaites, that is considered to be of utmost importance and has been given the ominous nickname “The Doomsday Glacier.”.

The Thwaites Glacier spans a width of 120 kilometers (75 miles) as it meets the ocean, stretching from West Antarctica into a basin located offshore. The increase in temperature of the air above and the water in front of the Thwaites glacier is leading to its melting; however, there are concerns about the possibility of a more severe outcome. The presence of water beneath the Thwaites glacier, which is currently located on the ocean floor, would subject the ice to increased heating, thereby significantly accelerating the rate at which it melts.

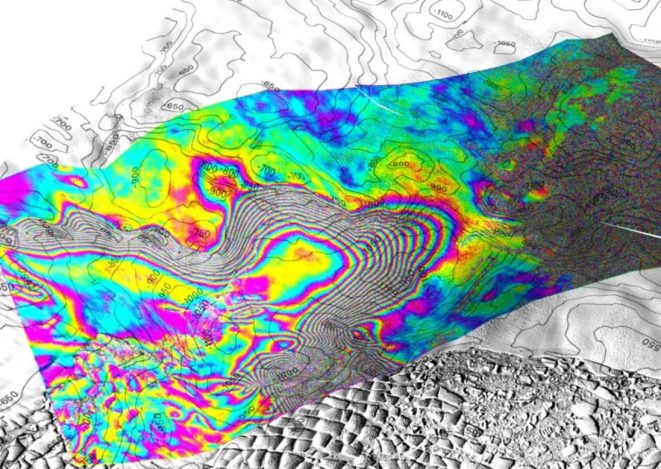

Professor Christine Dow of the University of Waterloo and her colleagues’ observations are relevant in this context. Based on satellite imagery, it has been observed that the water is consistently moving beneath the glacier, causing it to detach from the seabed. However, the glacier eventually settles back down due to its immense thickness of 1.2 kilometers (4,000 feet). The cycle of tides occurs regularly over a distance of 2–6 kilometers (1.2–3.7 miles) at the front of the glacier. However, during periods when the Sun and Moon are in alignment, creating extreme tidal conditions, the tides can extend up to an additional six kilometers.

This leads to a short period of rapid warming, but due to the shape of the basin, when the glacier’s front retreats further into the basin, the melting underneath will continue without interruption. The seabed is protected from accelerated melting by two ridges, which serve as the planet’s final defense. The question that humanity faces is the duration before both are violated.

According to Dow and his co-authors, this event is projected to happen within a time frame of 10-20 years, and it will result in a significant and rapid increase in sea level. “According to Dow’s statement, Thwaites is the most precarious location in the Antarctic and holds the equivalent of a 60 centimeters (24 inches) increase in sea level.” “There is concern that we are not accurately assessing the rate at which the glacier is undergoing change, which could have catastrophic consequences for coastal communities worldwide.”

While affluent areas such as the Netherlands and London may opt for the construction of dykes or tidal barriers, many other parts of the world will face the prospect of homes and valuable agricultural land being submerged.

Dow aims to enhance the accuracy of predicting the timing of these events by improving the models that simulate the movement of water in and out of the basin, as well as the mixing of saltwater and glacial melt in the area. “Currently, we lack sufficient information to determine the timeframe in which ocean water intrusion becomes irreversible,” she stated.

Nevertheless, the effectiveness of modeling is limited without the necessary direct observations to calibrate it. The scientific data from Antarctica used to progress at a rate similar to the movement of glaciers. While space surveillance has provided extensive information on certain matters, the same level of detail is not available for operations that necessitate physical presence.

“In terms of real dollars, our budget in 2024 is equivalent to what it was in the 1990s,” stated Professor Eric Rignot, the lead author from the University of California, Irvine. “To tackle these observation issues, it is imperative that we expand the community of glaciologists and physical oceanographers as soon as possible. However, at present, we are facing significant challenges that make it feel like we are attempting a difficult task with inadequate resources.”

The study is openly accessible and published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

Tech Gadget Central Latest Tech News and Reviews

Tech Gadget Central Latest Tech News and Reviews