We went to Amazon’s BOS27 robotics factory to talk about how package sorting and last-mile delivery are changing.

A tranquil town of 22,000 people, Westborough, Massachusetts, is located 40 minutes by vehicle southeast of Boston. One of the town’s more recent residents is BOS27. A little more than a year ago, the 350,000-square-foot Amazon warehouse began accepting customers. It’s a bulky, dreary addition to the landscape covered in trees. Inside is a cutting-edge laboratory that, along with a location in North Reading, Massachusetts, on the other side of Boston, forms the beating center of the business’s ambitious robotics goals.

Since purchasing Kiva Systems for $775 million in cash a decade ago, the company has expanded into one of the top robotics companies in the world. Any founder in the warehouse robots industry will acknowledge the company as the main force in the industry if you ask them.

At our robotics event in July, Rick Faulk, CEO of Locus Robotics, said, “We look at Amazon, perhaps as the best marketing arm in the robotics business today. “They have established SLAs that everyone must adhere to. And we consider them to be an excellent member of our marketing team.

In an effort to keep smaller businesses competitive with the retail giant, Amazon has set package delivery expectations at once-seemingly-impossible next or same day, and an entire industry has developed around it.

As soon as you enter BOS27, you notice how much the location resembles one of the business’s many fulfillment facilities. It is vast and alive with robots and the human counterparts to them. The company develops, tests, and constructs its robotic systems in the facility, which was constructed to house a business that had outgrown its single North Reading location. (An additional location recently opened in Belgium thanks to Amazon’s acquisition of Cloostermans in September.)

TechCrunch was among the media outlets allowed access to the company this week. By any standard, the “Delivering the Future” event was a PR campaign. It was a chance to showcase the business’s brand-new production facility and to promote Amazon Robotics, a category that now encompasses every aspect of the Amazon retail experience starting from the minute a customer clicks “buy now.”

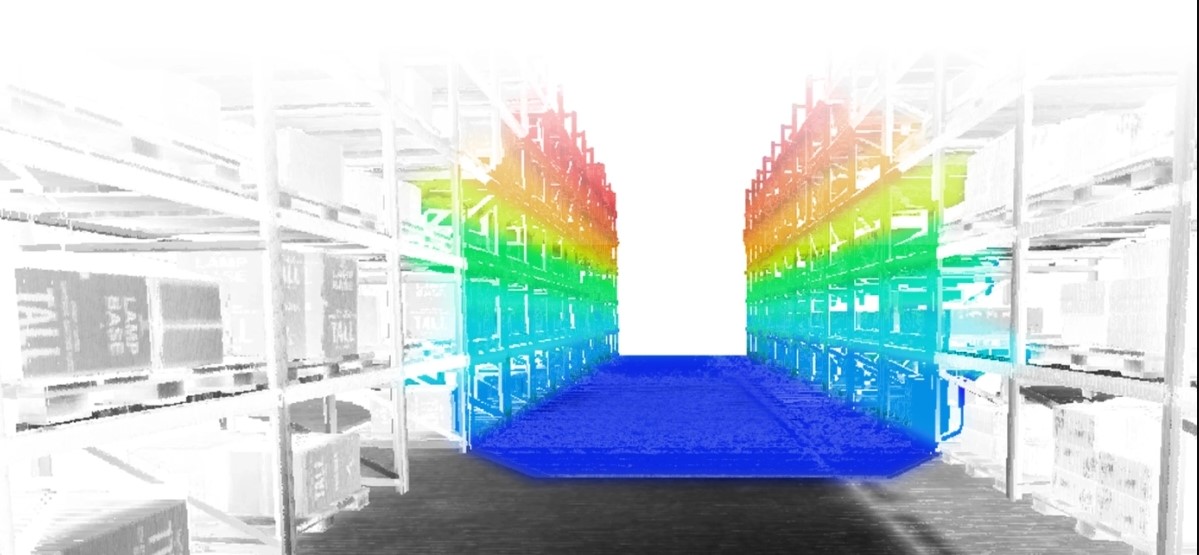

During a few guided tours of the floor, the company’s expanding fleet of wheeled robots constructed on the Kiva platform were on display. These included the omnipresent blue Hercules (the fourth-gen product), the miniature conveyor belt-mounted Pegasus, and the Xanthus, which is essentially a lightweight version of the latter. Proteus is a more recent entry to the market. It comes in an almost fluorescent green (or “Seahawks green,” as one executive jokingly referred to it today), has a small LED face, and is fully autonomous, allowing it to safely move outside the rigid boundaries designed for the older models.

A trio of robotic arms that Amazon also displayed displayed a similar evolutionary path to their wheeled counterparts. There is Robin, which made its debut about 18 months ago and is currently present in 1,000 warehouses worldwide. Because Cardinal compresses boxes firmly before sending them across the fulfillment center, it increases system efficiency. At the current event, Sparrow made his or her debut.

Like its predecessors, Sparrow is essentially an upgraded version of a Fanuc industrial robotic arm that is available off-the-shelf. The system is presently only being tested in a few places, such as a Texas facility and BOS27 inside a safety cage. But there are two things that make it different from Fanuc arm deployments as a whole. The first is the suction cup gripper, which picks up a variety of things using pneumatics.

Of course, the software is the true secret ingredient. According to Amazon, the system can recognize about 65% of the merchandise made available by the company when used in conjunction with a variety of various hardware sensors. It’s a staggering number. The system identifies unique objects by using factors including bar codes, size, and shape.

Robin and Cardinal only sell boxes, of which Amazon offers about 15 standard kinds. The much more difficult chore of collecting up the products themselves falls to Sparrow. Beyond identification, this poses a number of new difficulties. If you’ve ever bought anything from the company, you’re aware of how drastically the size, shape, and substance of these items can vary. Imaginarily, the same arm is picking up a bag of cotton swabs and a bowling bowl. The suction cup method can help with that because it provides a far wider variety of picks than a stiff robotic hand.

Since the establishment of Amazon Robotics in 2012, the company has deployed more than 520,000 robotic drives in total. According to the company, one of its robotic systems interacts with more than 75% of the products ordered through its website at some point.

The last mile was today’s event’s other main focus. The company has started deploying 1,000 Rivian EVs to meet demand for the holiday season.

Rivian said in July that “unique electric delivery trucks from Rivian will begin to be seen by customers across the U.S. delivering their Amazon deliveries,” starting with Baltimore, Chicago, Dallas, Kansas City, Nashville, Phoenix, San Diego, Seattle, and St. Louis, among other places. By the end of this year, thousands of Amazon’s customized electric delivery cars are anticipated in more than 100 locations, and 100,000 by 2030. This launch is just the beginning of that trend.

Unexpectedly, Amazon continues to have high hopes for drone deliveries in the future. In a keynote address, Prime Air VP David Carbon stated that flying was “a proved, targeted degree of safety that is recognized by regulators and a magnitude safer than driving to the shop.” By the end of this decade, 500 million parcels will be delivered annually by drones. operating in densely populated suburbs like Seattle, Boston, and Atlanta, serving millions of clients. autonomously flying in an uncontrolled environment

Although a mockup of the MK30 drone, which is scheduled to make its debut in 2024, did come on stage, one significant robot was absent. The sidewalk delivery robot Scout, for which Amazon recently put the brakes on severely, was not mentioned at all.

An Amazon spokesman told TechCrunch amid allegations of widespread layoffs, “During our limited field test for Scout, we attempted to develop a distinctive delivery experience, but realized through feedback that there were components of the program that weren’t meeting consumers’ needs.” We are discontinuing our field tests as a result and refocusing the initiative. Throughout this transition, we are working with employees to connect them with open positions that are the best fit for their expertise and skills.

Scout is by no means by herself. CEO Andy Jassy has been forced to implement evasive cost-cutting measures due to broader economic challenges. Among these is the closure of a number of divisions that were assessed to be operating poorly. Projects like Prime Air or Scout, which logically require a long runway, are difficult to see through this viewpoint (as do robotics and automation projects generally). Suddenly, even huge firms like Amazon are asking whether certain moonshot projects still have a chance of succeeding by considering sunk costs.

The ceremony was overshadowed by the background of these cuts. They offer at the very least a realistic perspective on these endeavors. It’s crucial to keep in mind that macroeconomic variables still affect large multinational corporations, even though they appear to have more wealth than god. From the outside, at least, it seems contradictory why a drone delivery program would be supported yet a robot for the last mile would be rejected, but this looks to be Amazon’s strategy for the last mile going ahead.

Tye Brady, the head of Amazon Robotics, and I had a brief conversation on robotic innovation against the backdrop of corporate cost cutting.

Brady told TechCrunch, “We’re clearly mindful of the macroeconomic situations that are taking place,” before adding that the business had recently frozen new employees until the end of the year. Amazon is undoubtedly not alone in that decision, and it hasn’t reduced its own workforce the way businesses like Meta have in recent months.

Brady said, “Regardless of the state of the economy, Scout has always been experimental. “We’re open to trying new things and experimenting. Both times and occasionally don’t work out. But we constantly draw lessons from our mistakes and apply them to robots.

Brady responded when asked if Scout was an instance of “things not working out.” “We conducted a few trials. We always ask, “How can we improve the customer experience?” as our final inquiry. The indications that we are observing might not be right now. Not now, though I’m not suggesting that’s always the case.

Canvas is even more integrated into the Robotics team. According to reports, the startup that Amazon acquired in 2019 for more than $100 million was among those affected by these cost-cutting efforts. A genuinely outstanding autonomous cart system had been created by the company. Over the summer, I was informed by VP Joseph Quinlivan that the Proteus system was created independently of the Canvas acquisition.

At the time, he stated, “That was internally built by the Amazon Robotics team that came out of the Kiva acquisition. “At Amazon, we frequently have multiple development projects underway. The Canvas team is going to concentrate on a different application that we haven’t yet revealed, and we’re excited to see what they deliver.

Brady claims that the Canvas team is not an example of a project, like Scout, that was just plain unsuccessful.

Canvas taught us a lot, the executive told TechCrunch. “We spoke with the team and observed the prototypes they had in mind. Even before Canvas was acquired, we had been working on prototypes for a while. We had the opportunity to discuss some of the technology and team’s practical insights. […] We’re leaning toward these experiences right now, but we’re also quite enthusiastic about the Proteus vehicle that just came out.

Brady claims that Amazon is “consolidating” its robotics initiatives under one roof as the business continues to curtail or halt other programs.

“Leadership, how we arrange ourselves to provide robotics products—both the ones you’ve seen today and any that we, hopefully, will announce in the near future. That doesn’t imply that our investment strategy will change. The need to invest in robotics is still quite great. Our belief that humans and machines can work together to accomplish tasks more safely, simply, and effectively has not changed in the slightest because of this.

Despite budget cuts, he continues, acquisitions are “always on the table.” In the face of larger cuts, Amazon is nonetheless preserving its $1 billion Industrial Innovation Fund. The corporation has already made investments in a number of robotics companies, including Israeli startup BionicHIVE and Digit-maker Agility, both of which create outstanding shelf-based robotic systems.

We understand that not everything needs to be created inside of Amazon’s borders, Brady added. “We can ride along with them if we can seed some of these startups and allow them to execute technology with a real project context behind it. If it makes sense, we can start incorporating those items into our own processes as they become successful so that we can learn from them as well. However, the actual purpose of the fund is to learn and observe what will transpire in this fantastic new golden age of robotics.

Tech Gadget Central Latest Tech News and Reviews

Tech Gadget Central Latest Tech News and Reviews